A Rugby Match

or the relationship between context and presentation

Every time I go back to England I seem to learn something new about myself. A few days after I arrived in early November, I had an essay published in The Guardian. In the printed edition it was a full-page article, which excited my parents beyond all reason, and my father duly texted my brother telling him to run out and buy as many copies as he could find. My brother declined, on the grounds that even looking at the Guardian raised his blood pressure (I love my brother unconditionally, but there are certain things of which we will never speak, and our political allegiances are one of them.) I then went to stay with him in London and he took me to a rugby match at Twickenham, one of the few things he and I used to do together when we were both in our twenties. Back then I’d wanted to be one of the boys, and resented being perceived as a girl at these very male-centric occasions. I’d always been curious about how it would feel to revisit that experience as the person I am now, so when my brother offered to get tickets I jumped at the chance. What I hadn’t accounted for was how incredibly heterosexual the type of men who go to rugby matches are. I’d dressed to match the occasion so I blended in with the crowd, but the knowledge that people automatically assumed I was the same type of man as these Guinness-drinking, straight men around me felt almost as uncomfortable as being perceived as a woman. And yet to present as a queer trans man felt both impossible and pointless. I felt different, and then ashamed that by trying to be different I was just being difficult: that any sense of exclusion I was feeling was somehow my own fault. It felt very close to the feelings of unresolved separateness I had in my twenties, when I was struggling to accept my identity.

Shortly after I returned to America I was invited to be a guest lecturer for a group of creative-writing students. One of them brought up a concern that I’d written about in Frighten the Horses, that if I transitioned my image would “become more important than I want it to be, because everything about the way I present myself to the world is now going to be a statement about who I am.” She wanted to know whether, eight years after I started transitioning, I’d found this to be true.

Of course, it had always been true, I just hadn’t fully understood the degree to which I’d already been subconsciously projecting the image of myself that I wanted to convey. Every choice I made about my appearance before I transitioned—the clothes I wore, the hairstyles I chose, the body shape I exercised or starved my way into—was performing a strategic function, whether I was aware of it or not. Since transitioning, I’ve become much more aware of the choices we all make in our presentation, constantly looking for the cues other people are giving off, and trying to ascertain what—and to whom—they’re signaling. I don’t know why I never noticed it before, but I think I’m hyper conscious of it now because I spent so much of my life trying to present a false image of myself to the wrong people.

I saw an Instagram reel a few days ago by a woman who said she was dressing for herself, not for men. I understood the point she was trying to make, but I question whether, when anyone says they dress for themselves, they’re telling the whole story. To “present oneself” requires an audience, and as the pandemic taught us, if the audience was only ourselves we’d spend every day in pajamas or sweatpants. What this woman was more likely trying to say was that she was trying to project the image of who she is, not the image of what men would like her to be. She was prioritizing her own identity over projecting a false self to attract a mate, which was probably why she looked so great.

You know that feeling you get when you see someone walking down the street in a fedora, and you get the sense that the hat is wearing them, rather than the other way round? Usually it’s because that fedora is who he wants to be, not who he is. When I was falsely identifying as female I always felt like my clothes were wearing me. I misunderstood my vast and eclectic wardrobe from my pre-transition years as an attempt to “look good” (by which I mean attractive, stylish, individual) when in fact what I was searching for were clothes in which I could feel like myself. I didn’t find them, of course, because I was looking in the wrong section of the store.

My “adolescent phase” after I transitioned was mostly spent trying to replace my wardrobe, but after a few false (and sometimes embarrassing) starts, I’ve now found my comfort zone: a mash-up of 80s London hard-mod-revival and archetypal literary professor (I am not a professor) invoked by a combination of Doc Martins boots, turned-up Levis, and tweed or wool jackets. I favor linen shirts rolled up to the elbows to show off my tattoos and a particular brand of tortoiseshell glasses that can only be found at Fabulous Fanny’s in the East Village. I wear Velvet Orchid by Tom Ford because I haven’t been able to relinquish the desire to smell nice, and I carry my voice with pride because in New York my British accent makes people think I’m more intelligent than I am, plus the pitch of my voice implies queerness, even if it’s not immediately apparent whether I’m trans or gay.

All of these choices are an attempt to signal that I’m the sort of person whose music taste extends from The Smiths to Donizetti, who’s middle-aged but not that middle-aged, who’s favorite hobby is reading but the reading material is more likely to be Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore than Martin Amis. My whole presentation tries to combine as many of the different elements of my identity as possible—male, queer, English, writer, liberal—to give you the fullest picture of who I am in a single snapshot.

However, when I transport this picture from America over to the UK, I run into problems. Over there my image is outweighed by my accent, which in England is immediately identifiable as received pronunciation, the marker of someone who’s been privately educated. The assumption that I am both wealthy and politically conservative is made as soon as I open my mouth, because people see what they’ve been trained to see: they notice the signals they can read, and ignore the ones they can’t. English people hear my voice first, and then everything else about me is processed in relation to that, so my tweed jackets now signal conservative wealth, and once you factor in the fact that I’m white and male—and because generally speaking upper-middle class society is not a hot-bed of radical queerness—all my other signals (tattoos, tortoiseshell glasses, effeminate mannerisms) might as well be invisible. “Nobody knows I’m gay” is a popular t-shirt, but add to this “nobody knows I’m left-wing, feminist, anti-patriarchy and pro-Palestine” and you get the idea.

It’s an unpleasant feeling - not the same as gender dysphoria, but eerily close. It reminds me of how invisible I used to feel before I transitioned: not the comfortable sort of invisible I get in New York where nobody notices me because I blend into the background so easily, but the uncomfortable sort of invisible where I don’t quite feel real because I’m not sure anyone can actually see me. It’s not as bad as being mistaken for a woman, but it’s triggering just the same.

Still, it makes me realize that the concerns I voiced back in 2017 were unwarranted. My gender dysphoria is gone, and that’s much more important than whether or not I feel comfortable at a rugby match. Ultimately, the only signifier that really matters is the one that conveys my maleness, and that seems to be working fine, whichever country I’m in. I don’t think I truly understood in 2017 how comprehensively people would read me as male once I’d fully transitioned, because at the time I was afraid of taking testosterone, so I believed that if my body was still nominally female-looking (altered by top surgery but not hormones) I’d have to spend the rest of my life actively signaling my masculinity through my clothes and behavior. After almost six years on T, however, my receding hairline, visible stubble and lowered voice does all the work for me: significantly more, as it turns out, than my masculinized chest, which you can only see if you’re fortunate enough to see me in my underwear, which at the moment precisely zero people do.

So while lazy assumptions (about class and political affiliations) can sometimes be annoying, at other times (about gender) they work in my favor. Which goes back to why I have so much admiration for people who identify as non-binary, or trans people who don’t pass. They don’t have the luxury of being able to fall back on tropes or generalities to project their identities: everything about how they present has to actively work against other people’s assumptions about gender, all the time.

When I returned to New York, the first thing I did was go to Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore’s book launch at The Strand. The utter relief of being in a room full of queer people cannot be understated: all my signals were magically working again, and I felt that glorious feeling—which will never grow old—of being seen and known and understood. This is why queer, literary New York will probably always be my favorite community in the world. Sometimes context is everything.

Love, Oliver

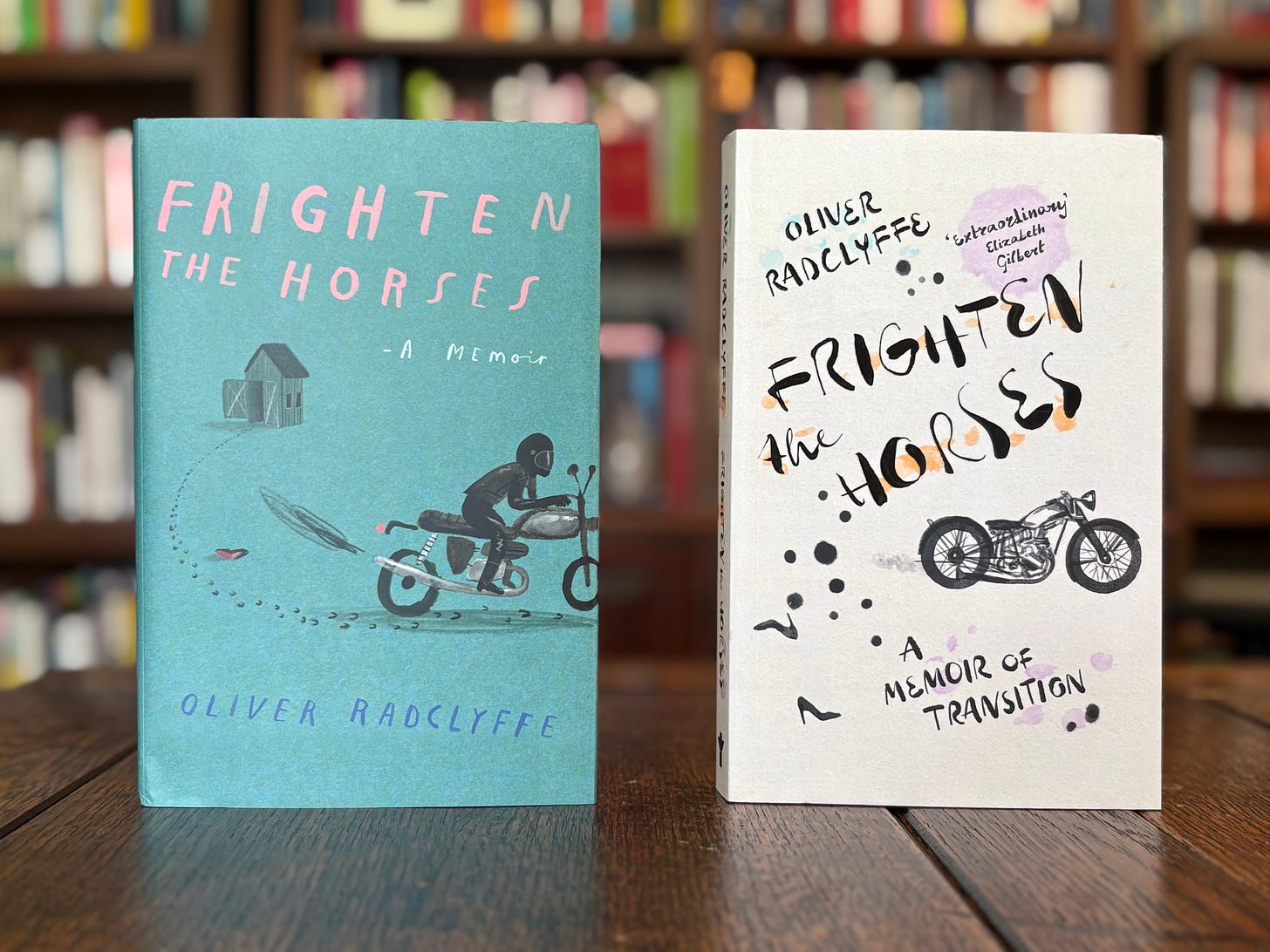

I’d like to keep these posts free for everyone, but if you’d like to support my work as a writer, please consider upgrading to a paid membership, or buy a copy of my memoir, FRIGHTEN THE HORSES—an Oprah Daily Best Book of Fall—which is out now in paperback with Roxane Gay Books in the US and Grove Press in the UK. A valuable alternative narrative to the loss and pain that queer history has too often insisted on — New York Times; Humorous and heartwarming — LA Review of Books; It’s the voice that makes this memoir stand out. This is a writer who can capture any moment with a dazzling, insightful, at times musical phrase — Oprah Daily; This book is sharp as razors, but it also pulses with a passionate, desperate, human urgency for truth and liberation — Elizabeth Gilbert; The finest literary telling of the experience of gender transition that I’ve ever read — Kate Bornstein

A good piece Oliver. It reminds me of a bit of advice handed out to trans folk in the 90's: always to make sure you were looked at before you began speaking. Which I can vouch for. I very much agree that being a stranger in a strange land is a serious layer of protection/ deflection. Here in Belgium people don't get past my 'sarff Lundun' accent, which they always seem to love and see as charming and authentic, unaware of so much of the British class thing implicit in it, which they don't see. They are unseeing because I had a good post graduate level art school education and I am seen as a painter (which is another layer of deflection in itself). In reality I come from a fallen lower middle class - the family was Waterloo based and ran a pub opposite St Pauls and they were bombed out in the blitz and relocated to Biggin Hill of all places, thinking they were safe out in the sticks - my mum came from a farming family from the London suburbs and so I am working class largely because I grew up in a council house. There are echoes of Eliza Doolittle here no doubt. But it's a good defence. Thirty years post transition and despite having very good speech therapy that my Lambeth based GP sourced for me at St Thomas's Hospital I often get called sir on the telephone, because after all this time I've settled for a pitch between my old voice and the higher one I was taught I could access at speech therapy because it seems more natural and honest - I'm done with acting. If someone on the blower calls me sir I let it go, although, if the conversation demands it I just tell them I'm trans. I'm now secure in who I am, but in my trans adolesence it would sting like hell, but I grew past it...you have to because in this game if you don't toughen up you will not make it. Take care in the Orange Ogres New Kindom!

I’ve only just discovered I can ‘like’ these musings, which I have been very much loving since you started them. So happy you are back in your community…and not totally surprised that Twickenham wasn’t exactly your scene. HOWEVER the women’s rugby was a complete triumph of both women’s prowess at the game and the queerness of sport. Some teams were 50-60% queer I think. You need to switch your gender allegiance!