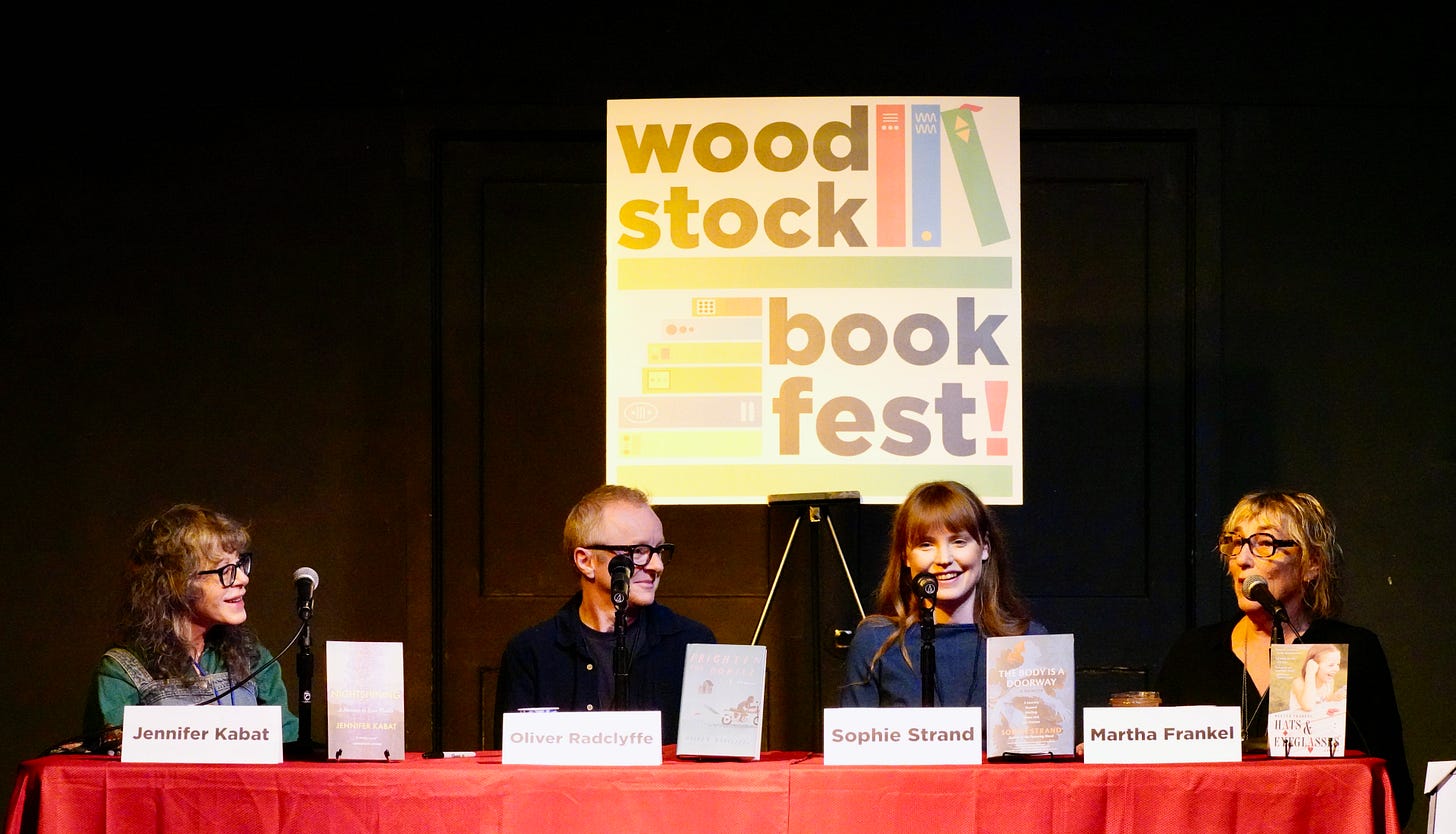

Last weekend I was on a panel at the Woodstock Bookfest, which marked the end of my book tour. It was a lovely way to end since I have many friends up there, Martha Frankel who organizes the event is one of my newest favorite people, and the Golden Notebook, one of the many sponsors the festival, is my oldest favorite bookstore. But this also marks a return from being an extrovert to being an introvert again, since when one book ends, another must begin, and that internal shift I had to make from being a writer sitting at a desk to being a writer out on the road now has to happen in reverse.

The best part of promoting Frighten the Horses has been all the people I got to meet. Trans people, trans allies, parents of trans kids, regular people who just like reading, other writers promoting their own books, the various people who work in the publishing industry, the events organizers and venue staff and book sellers who make it all happen… every single person I met on this tour was utterly delightful and I feel completely rejuvenated by it all. It’s been a lot of human interaction after years of partially self-inflicted, partially unavoidable solitude, and it’s been a LOT of fun.

The hard part of promoting a book, however, is worrying about sales, which is no fun at all, and plays havoc on one’s anxiety levels. The best way to lower anxiety, I’ve found, is through intense focus on a single activity, but while writing a book is all focus and no ego, promoting a book is all ego and no focus. A perfect breeding ground for future-tripping, and not in a good way. How many people are buying the book? Will I earn out? If I don’t earn out, will I be able to sell my next book? If nobody acquires my next book, is my career over? If my career as a writer is over, what the hell am I going to do with the rest of my life? Follow this to its natural conclusion and I end up dying miserable and alone. Fun stuff.

But as Jonathan Crary recently said, “Each of us is demeaned by the veneration of statistics - followers, clicks, likes, hits, views, shares, dollars - that, fabricated or not, are an ongoing rebuke to one’s self-belief.” And a lack of self-belief, as every writer will tell you, is the biggest impediment to opening up that fresh new page and starting to write again. Over and over I’ve had to remind myself that I successfully managed to write for ten years without knowing whether I’d ever get published—without knowing whether my writing was even any good—and I have to accept that process will begin again every time I start a new manuscript. There will never be any guarantees. That’s why this is such a brilliantly, insanely, terrifyingly evil vocation to be chosen by. It’s probably also why I love it so much.

So now I’m back at home, working on the first draft of my first novel, and beginning to realize how much the discipline I developed while writing Frighten the Horses is helping me stay sane through our current political situation. As the sole parent of four children, I had to schedule my writing hours every morning—and stick to them—or I’d never have finished the manuscript. During those hours I had to learn how to shut out all the external noise—my children’s needs, my anxiety about their needs—or I couldn’t disappear into that part of my brain that blindly produces words out of nothing. I had to get eight hours sleep because I know that’s the minimum on which my brain can function clearly enough to free-write, and I had to learn how to compartmentalize, to separate my writing world from the real world, and to be able to switch quickly between the two. In a strange way, being a working parent was laying some pretty good groundwork for learning to live under an authoritarian regime without losing my mind. After all, what are kids if not a bunch of wanna-be authoritarians? And what is writing if not an act of resistance, of holding on to something personal only for yourself?

In a moment of despair earlier this week I did, however, wonder whether I’d have to log off the news cycle completely in order to be able to sufficiently lose myself in this manuscript. I can’t draft when I’m anxious—when the noise in my head gets too loud and the wires feel like they’re crackling with static electricity—but what’s happening in America now is a crucial part of the novel I’m writing, so technically reading the news qualifies as research. Plus, as the trans writer Denny said yesterday in her essay for 100 Days of Creative Resistance, “I’m afraid in our attempt to protect our sanity by staying out of the loop, we are inevitably resorting to ignorance.” Somehow I have to find a balance, which I’m fairly confident I will. I’ve become pretty adept at adjusting my life to new circumstances.

In the end I sat with my anxiety for long enough to identify that I was picturing a future in which everyone I cared about was forced to leave the country, and that my whole community was about to disappear off to various different corners of the globe, never to be seen again. Aware that catastrophizing is my brain’s response to unidentified fear, and that isolation is not a terribly good cure for loneliness, I texted a friend, who immediately called me back and sweetly reassured me that, at least for now, they weren’t going anywhere. The permanent sense of impending doom/nameless loss hasn’t quite disappeared, but after this one brief conversation with someone I care for deeply, it now at least feels more manageable. I know you’re hearing this a lot from me, but it bears repeating: community is what’s going to keep us all sane through this. Caring for other people, and allowing them to care for us, including, wherever possible, real in-person, human contact, is not just important but necessary. Go hug a friend. Or your partner, or your kid, or someone else’s dog. It does help.

The book I’m currently reading, Kairos by Jenny Erpenbeck, is also fueling my determination to keep writing. The novel is set in East Berlin in the 1980s, where the restrictions of life under a communist regime have become so normalized they’re almost unnoticeable to the characters in the story. Dotted here and there throughout the arc of an ill-fated love affair are moments when the reader is reminded that the protagonists are trying to navigate more than just their unravelling relationship:

“Han’s former lover Sylvia talks of ‘pink elephants,’ which is her term for sentences and paragraphs she writes into program scripts so that there’s something to remove. Meanwhile, it’s the shears in her head that are the real problem, she says. Hans knows she means a galloping anticipatory obedience, but still has a momentary vision of a pair of shears caught in the windings of Sylvia’s brain. In the Writer’s Union someone reads a resignation letter from a colleague justifying his leaving the Theater Group. Mind-boggling, Hans hears a woman say in the row behind him. And the abolition of the so-called approval process for literary texts—censorship to you and me—was long past due.”

These moments feel shocking, not only because they’re dropped into the narrative so casually, but because they could so easily describe a state of censorship we may soon find ourselves living under. Later in the chapter, Erpenbeck writes, “Maybe Gorbachev in his declaration regarding ‘free sovereign elections’ was recalling what Lenin wrote in his philosophical manuscripts: There is no doubt that the spontaneity of a movement is an expression of its deep roots in the masses and makes it impossible to expunge. Unfortunately, there’s nothing there about the quality of such a spontaneous movement. Hitler came in through the ballot box.” It’s uncanny how prescient that now feels.

Towards the end of her essay for 100 Days of Creative Resistance, Denny suggests that we should “write as if we have made it through to the ‘other side,’ because the ‘other side’ is just a fantasy. The truth is that we will never reach it. So why wait for things to get better, when your art is the very antidote to getting us as close to the ‘other side’ as possible?”

To that I’d add: write as if censorship is just around the corner. Because if they’re censoring our speech today, they’ll be censoring our writing tomorrow.

Love, Oliver

I’d like to keep these posts free for everyone, but if you’d like to support my work as a writer, please consider upgrading to a paid membership, or buy a copy of my memoir, FRIGHTEN THE HORSES—an Oprah Daily Best Book of Fall—which is out now with Roxane Gay Books in the US and Grove Press in the UK. A valuable alternative narrative to the loss and pain that queer history has too often insisted on — New York Times; Humorous and heartwarming — LA Review of Books; It’s the voice that makes this memoir stand out. This is a writer who can capture any moment with a dazzling, insightful, at times musical phrase — Oprah Daily; This book is sharp as razors, but it also pulses with a passionate, desperate, human urgency for truth and liberation — Elizabeth Gilbert; The finest literary telling of the experience of gender transition that I’ve ever read — Kate Bornstein.

Am devouring your book and am delighted at the chance to hear you via Kyle’s book club next week. Thank you for your words and for your insistence that we keep writing.

LOVE the peek into your writing world and a view of all those shelves. Going to make a note to ask you about the art on your walls when we meet later this month.