When I went to see the recent Jeff Nichols film The Bikeriders, I was hoping for a trip down memory lane. Back in London in the 1990s we didn’t have motorcycle clubs as such — with their bylaws, “colors” and chapters — and our bikes were more likely to be Suzukis or Ducatis than Harley Davidsons. But motorcycles are motorcycles, and I was looking forward to indulging in the unadulterated masculinity of it all, reliving those long-lost feelings of euphoria and freedom.

The members of the Vandals, the motorcycle club in The Bikeriders, had banded together in response to a specific male need: the deep-rooted desire to belong, to be part of a gang. When I was in my twenties, I too wanted to be one of the boys, and buying a motorbike seemed to be the obvious way to achieve this ambition. But unlike Tom Hardy and Austin Butler, I was not a six-foot hunk of hairy, muscled manliness. I was petite, slim-figured, and five-foot-three, and I’d been assigned female at birth.

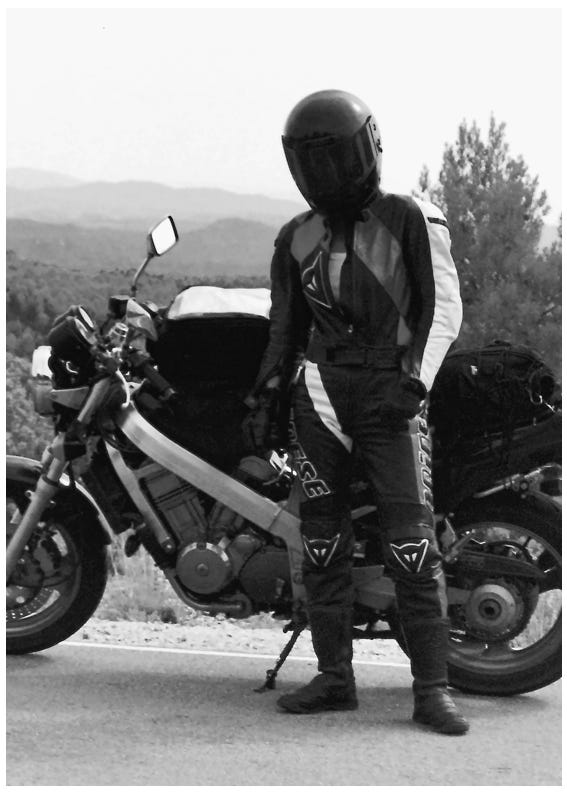

Back in those days, when anyone thought of a girl on a motorbike, they immediately pictured the singer Marianne Faithfull. Because I had long blonde hair, the comparison was heightened, so I solved the problem by cutting it all off. I bought racing leathers which hid the curves on my chest and hips, and a full-face helmet which concealed the femininity of my face. Speeding through the English countryside at a hundred miles an hour, nobody could tell me from the men I rode with.

When my biker friends and I went to motorcycle festivals and shows, some of the other girls in the group changed out of their leathers and into dresses as soon as we reached our destination. I thought they were insane. The whole point of being in this gang was to demonstrate that I was as good as the boys, why would I want to draw attention to my gender by dressing like a girl?

I rode my own bike, bought my own drinks, and held my own opinions. I had something to prove, although at the time I didn’t fully understand what it was.

Fifteen years later — now married to a man and presenting as ultra-feminine to assimilate with the heterosexual suburban crowd — I took my children to watch a motorcycle rally which was due to ride through our small town on the Connecticut coast. As the motorcycles appeared over the hill, I was hit with a destabilizing blast of nostalgia: cigarette butts and motor oil on the floor of the garage where my friends cleaned their carburetors, fry-ups in the greasy spoon cafe where we went for breakfast before each ride, the weightlessness of a one-ton machine hovering above the ground at lawless speed. It was like being transported back to the person I’d once been, and the shock of seeing myself clearly — and realizing that underneath all the feminine trappings I was still that person — felt like a bucket of cold water in my face.

Prior to that moment I hadn’t known I was trans, because coming of age in England in the 1980s I didn’t know trans was a thing you could be. Trying to figure out why my identity felt so messed-up had been like trying to assemble a V-twin engine in the dark. Not only did none of the pieces fit together, I had no clear picture of what I was attempting to build. But because trans identities had become so much more visible over the intervening years, I could now see who — and what — I was.

One ex-husband, several girlfriends, and a gender transition later, I finally understood what it was I’d been trying to prove. The cliche of motorbike as penis-extension was as true for me as it has ever been for any man: I was quite literally trying to compensate for a part of my body that was missing. In retrospect this is so blindingly obvious it seems laughable, and yet reducing the experience to a phallic joke doesn’t fully explain why my gender dysphoria magically disappeared every time I got on a bike.

The performative side of motorcycling — the tribal masculinity — was central to the plot of The Bikeriders. This I could relate to, since being a biker became my identity for many years. Even when I wasn’t on my bike, carrying my helmet in the crook of my arm was a way for me to signal my status, in the same way the bikers in the movie signaled theirs via the insignia on their leather jackets. I wanted the world to know that I was one of the boys, regardless of my gender, and that they should adjust their expectations accordingly.

But there’s another, more elemental aspect to motorcycling that the movie missed entirely, perhaps because Harley Davidsons are built for cruising, whereas Italian and Japanese bikes are built for speed. Riding a motorbike designed for racing is a whole-body experience. You don’t steer a motorbike at high speed, you move it with your muscles, as if the machine is wired into your central nervous system and your mind is directing it like a giant bionic limb. If you want to corner to the right, all you do is tighten your thighs, exert light pressure on the front of your left handlebar, lean the bike over as far as you dare, and your body does the rest. It sounds counterintuitive, but once you let yourself trust the process the feeling is exhilarating.

What I experienced at the motorcycle rally wasn’t just a desire to be one of the boys, or even to have a girl on the back of my bike, it was a nostalgia for that feeling of wholeness. The euphoria I felt when I was on my bike wasn’t just because my gender was hidden beneath a full-face helmet and an armor of leather, it was because it was the only time my body worked with me rather than against me, the only time I got any joy out of having a body at all.

In retrospect, the synchronicity I developed with my machine may have been a trial run for learning to live in a post-transition body. Biking brought me back into myself, it pieced me together at a time when dissociation was my default setting, it made me feel like my body had a place and a purpose in the world. Regardless of how dangerous it is, motorcycling may have saved my life.

When a friend asked me recently whether I’d ever get a motorbike again, I wasn’t sure what to answer. I don’t need a bike to prove my masculinity to other people anymore, or to feel aligned within my own body, and I have a greater investment in my own physical safety now that I’m a parent.

Still, in my quieter moments, I occasionally fantasize about flying out to Italy, hunting down that elusive 3 ½ Sport, and taking off down the twisty mountain roads. However comfortable I may be, motorcycles will always mean freedom to me, and a man can always dream.

All photos taken by me at various British motorcycle rallies in the 1990s.

To read more about my days as a biker, order Frighten the Horses here: