I’m typing this at the kitchen table in my parents’ house, having flown in from New York late last night. Standing in the middle of the front lawn with my cup of coffee earlier this morning, I felt the near-constant anxiety I’ve been feeling about the political situation in the US begin to dissipate slightly. It’s a Pavlovian response I always get when I come here, particularly at this time of year when the primroses are out, and the skies are clear, and all you can hear is birdsong. Right now this brief escape from reality is particularly welcome, but I do know this is an ivory tower, a place of privileged seclusion that is occasionally lovely to visit, but—given the person I’ve become—not somewhere I can stay for long.

I can’t write about the level of fear I had after watching the meeting between Trump and Zelensky yesterday because I can’t yet find the words, but it occurred to me while I was standing on the lawn this morning that the adjustments we’re all trying to make to this new world order are, in a strange way, similar to the adjustments trans people have to make when they transition. The old, normal world falls away, and there’s a period of wild disorientation while you try to adapt to the new one. You have to figure out what kind of person you’re going to be, what you have to give up, what you must fight for, how to take care of the people around you while you’re going through it, and how to be true to yourself. Currently everyone I know is experiencing a speeded-up version of this process, with zero preparation, against their wishes. No wonder they’re all freaking out.

Community is the word on everyone’s lips at the moment. The trans community is under attack, the trans community must band together, the trans community needs support. Because I don’t feel qualified to write about what happened yesterday, I’m distracting myself by trying to figure out my place within the trans community—not among my immediate queer friends, but in the larger scheme of things. My connection to trans history. Every time I come back to my family home I’m reminded that I come from generations of colonialists and white supremacists: my father hates hearing them called that, but that’s what they were. I love my family, but I’m not proud of my lineage. I severed myself from this line when I decided to come out as queer, but while reading Robert Jones Jnr’s The Prophets last year, I wondered what it would feel like to have ancestors who would understand and embrace the person I am today, to have ancestors I could pray to in times like these.

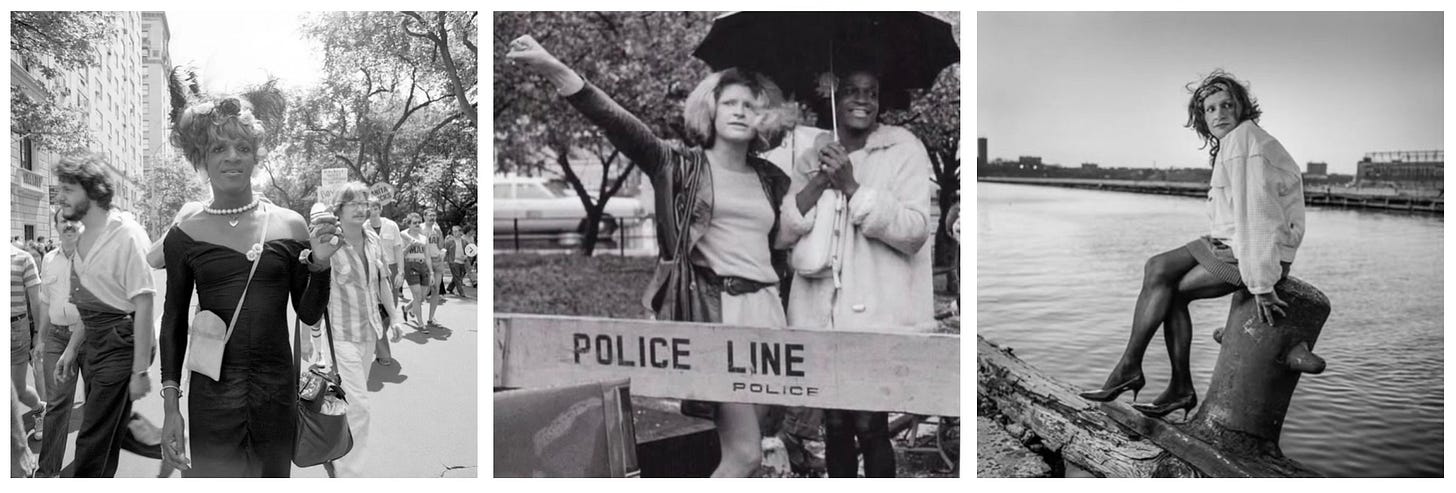

Much has been written recently about our trans ancestors—particularly this great piece from Gillian Branstetter inspired by the attempted erasure of trans people from the history of the Stonewall Inn—all of which left me wondering (not for the first time) whether this is a lineage I’m allowed to call myself a part of. Trans people don’t claim their ancestors through blood genealogy, but through shared experiences, and as a middle-class, able-bodied, white trans man, there is a limit to which I can reasonably claim to have shared experiences with people like Sylvia Rivera, Marsha P Johnson, or Leslie Feinberg. These are people whose unwavering perseverance and courage in the face of almost unthinkable levels of public opposition makes any small act of defiance on my part feel like child’s play.

And yet I transitioned, which, let’s face it, is a pretty wild thing to do. At first glance I don’t look like a very radical person, but then I never saw my transition as a “radical” act in the political sense of the word, because I wasn’t trying to make a political statement, I was just trying to make myself into a whole human being. My sense of myself as the living embodiment of a political position only came later. My experience as a queer person, although arguably a story of of loss, was never one of danger. I was safe during the AIDS crisis because I hiding in my closet, and I’m safe now because I’ve fully transitioned. To all intents and purposes, I’ve assimilated. The assimilation wasn’t intentional—in order to transition I had to let go of any hope of social respectability—but it happened anyway because I pass so easily as a man. I’m a father, I live in the suburbs, and apart from a few tattoos I basically dress like my Dad. My radical interior is belied by my very ordinary exterior.

This makes me far less vulnerable than many other trans people are, as does my age, my location, and my access to resources. Which means that whenever I refer to trans people using first-person plural pronouns or prepositions—we or us—I’m aware there’s a marked difference between what I’m going to experience over the next few years, and what many other trans people are going to experience. But I’m not the same person I used to be when I lived here, in the seclusion of the English countryside, because now my concern no longer stops at my own safety: I’m not giving up until every trans person can enjoy the same levels of protection that I have. Also, I’m beginning to realize I may not be as safe as I think I am. I’m having a bit of a hard time getting my head around that, to be honest.

Either way, the truth is that I wouldn’t be here today without Sylvia, Marsha, Leslie, and all the thousands of other recognizable and anonymous trans people who came before me. I only transitioned once I saw that it was feasible, and that only happened because someone else did it first. If our ancestors can be defined as those who made it possible for us to have life, then I think I’ll give myself permission to claim these people as my own. I may be needing them to pray to in the future.

Love, Oliver

I’d like to keep these posts free for everyone, but if you’d like to support my work as a writer, please consider upgrading to a paid membership, or buy a copy of my memoir, FRIGHTEN THE HORSES—an Oprah Daily Best Book of Fall—which is out now with Roxane Gay Books. A valuable alternative narrative to the loss and pain that queer history has too often insisted on — New York Times; Humorous and heartwarming — LA Review of Books; It’s the voice that makes this memoir stand out. This is a writer who can capture any moment with a dazzling, insightful, at times musical phrase — Oprah Daily; This book is sharp as razors, but it also pulses with a passionate, desperate, human urgency for truth and liberation — Elizabeth Gilbert; The finest literary telling of the experience of gender transition that I’ve ever read — Kate Bornstein.

I refuse to believe that this is the new world. We still have a chance to fight and you're doing a great share of the fighting. Frighten the Horses will forever have a place on my mental bookshelf right next to Hesse's Siddhartha. Thank you for your work and for sharing your beautiful soul with us.

Thank you, Oliver. We're all upside down, I fear. I couldn't watch what happened in that disgusting display by the idiotically elected traitor and his veep. It's tragic beyond words that this is what we've got in office.

Sending you support from New York. Reading your book at present and loving it. It's a gift to anyone who picks it up.